January 25, 2021

Be the first to know about the latest artist news and gallery events by signing up for our weekly newsletter

Keith Sanborn [KS]: Your newest works bear connections with some of the earliest interests of the Situationist International. In particular, they emphasized the relationship of people to the urban milieu, and what they called psychogeography. The pandemic has caused a radical alteration in this relationship.

Anton Ginzburg [AG]: Staying at home during a pandemic made me think about my immediate environment and the modernist architecture I was surrounded by. The building I currently live in is Chatham Tower in downtown New York, a brutalist tower built in 1969. That era was characterized by the threat of the nuclear war with the Soviet Union during the Cold War — the proportions, tectonics, and aesthetic choices remind me of a massive bomb shelter. Staying quarantined indoors, I turned to reading the manifesto published by the Situationist International, entitled “Formulary for a New Urbanism, 1959”, which had been written by Ivan Chtcheglov. I found some interesting coincidences; when he writes about modernist architecture (for example, Le Corbusier buildings), he states that they arouse in him the idea of immediate suicide. That is, that the last remnants of joy were destroyed. And as it happens, I live right across the street from the prison where Jeffrey Epstein recently committed suicide.

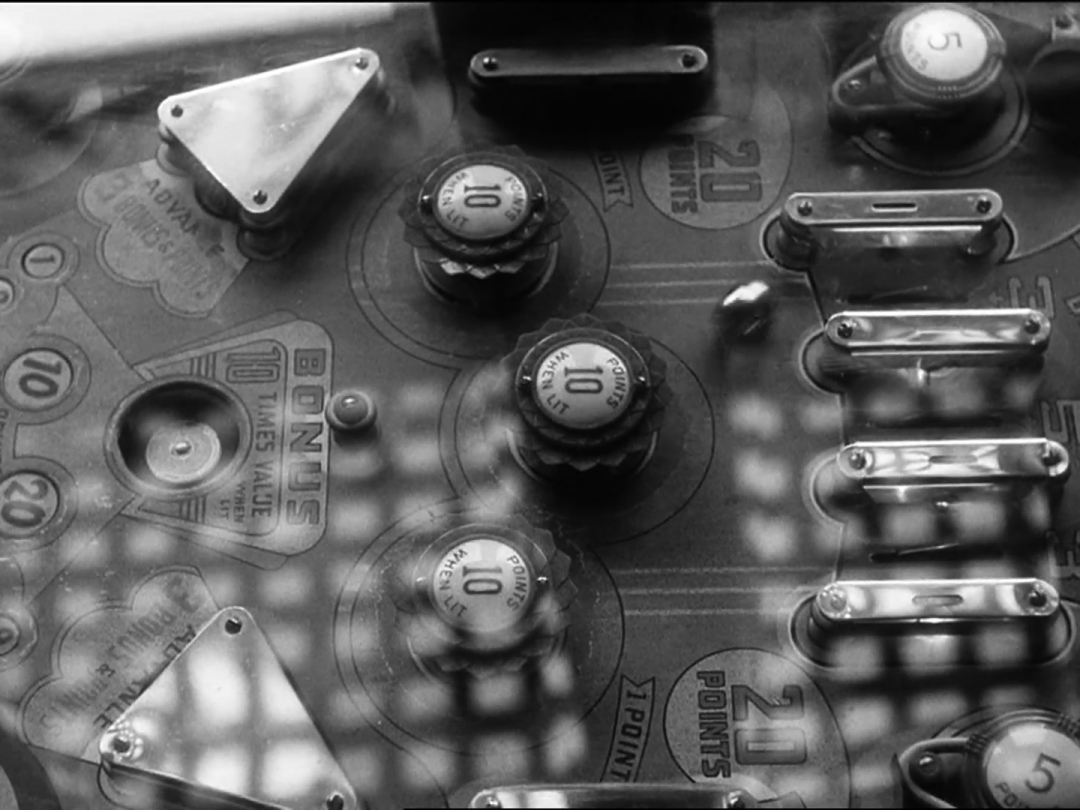

KS: In a short essay entitled “Introduction to the Continent Contrascarpe,” Chtcheglov says, “Once economic problems are resolved, geography is destiny.” He offers this image: “Our adventures resemble the magnetized balls of pinball machines with unaccountable trajectories, which are nonetheless, calculable.” A metaphor he relates to Debord’s unrealized project for a kind of psycho-geographical pinball machine based on a time of day and a place in Saint-Germain-des-Pres. Chtcheglov’s key insight is about the relationship between individual subjectivity, the social, and the architectural determinants of consciousness. One could take the octagonal shape of your paintings as a given, like urban space. One doesn’t have to be so strict about the analogy, but color and the forms within the octagon function as a kind of expression of calculated subjectivity in response to that given.

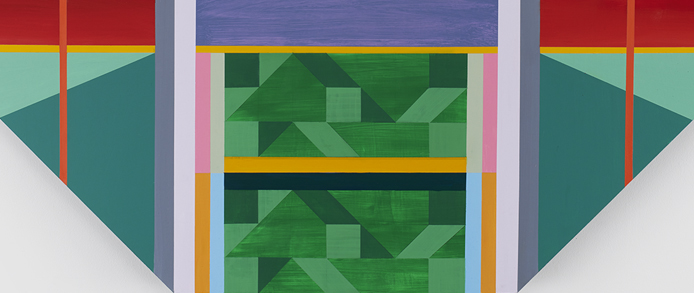

AG: For me, the octagon shape of the paintings can work on two levels: it can represent a modernist tondo, or an architectural detail. It has the stability of the square and reference to the window and the diamond shape's dynamism. The shape of the paintings emphasize modularity and also set a grid that my compositions interact with, while the colors introduce the subjectivity, premise of space and emotional affect.

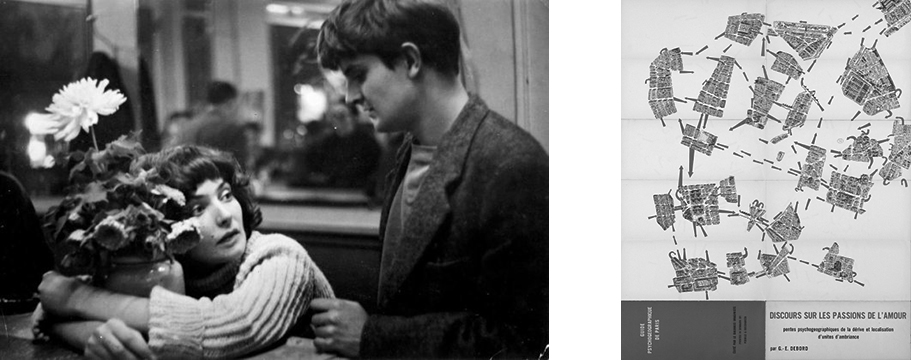

KS: Your reference to the tondo is singularly apposite, as the tondo often appears in an architectural setting. The paintings could also be thought of as maps, but they’re not maps of geographical locations. They might be thought of as maps of psychic locations, or psychological locations. They are mental maps. We have the possibility of either looking down from above or looking directly at them. They suggest an illusion of perspective space, but they could also be taken as flat architectural elevations or overhead views. And again, Chtcheglov enters the picture with the collages of maps he and Debord were making around the same time he was writing “Formulary.”

Whenever I see an octagon, I see a stop sign, though in a gallery space, that effect might be mitigated. Nonetheless, the octagon is a constraint. And within it, you have inscribed triangles as well as squares. These function as acts of resistance, or at least a strategic response to the constraint of the octagon.

AG: I used a Constructivist pattern here that I believe was designed by Liubov Popova. The paintings are structured, so there is a relationship between the interior and exterior. I think of the central parts of the work as representing interior spaces or inner states. The side panels along the outer edges describe outdoor spaces and architectural facades. Besides the rhythm it creates in the painting, the pattern also serves as a floor's flat surface, challenging the figure-ground relationship.

KS: In one of the still-extant fragment of a novel that Chtcheglov wrote, he remarked that “the search of the man towards the center is easy; that of the couple towards the periphery is not.” He was speaking about a romantic, medieval quest. But that relationship between interior and exterior space, and the traversing of space from the exterior to the interior—the outward dynamism towards the edges. I think that's an interesting observation, both in terms of the compositions of these paintings, as you're talking about them and in their effect, their psychogeography. This tension between center and edge, romance and adventure, surfaces again in your video, Constructivist Drift.

AG:I would also connect it to the time aspect of the artwork. While the duration is more apparent in the video, it is also an essential factor for the painting. How a painting is experienced, its immediacy, density aligns with what you mentioned earlier about it being a mental map.

KS: Well, I thought it was interesting, for several reasons. The relationship to the architecture surrounding you is the main thing, but the woman in it evokes a romantic quest, or at least a reality which is related both to buildings and to persons.

Ivan Chtcheglov, detourning Freud, summarized a great deal by saying, “geography is destiny.” In his case, this formulation summarized a failed attempt to view a particular landscape. He and a woman, his lover, were in the south of France, and they wanted to travel to a particular place to see a location that had appeared in a film. They were told at their hotel, that no cars were available to rent. So, she went to the movies instead by herself. He went to the train station to try to rent a car, and it turned out the cars were available. But it was too late. The moment was lost. For Chtcheglov, misinformation and geography combined to create a disconnect. And the inability to complete that journey together led to the falling apart of the relationship. The psychogeography of the movement through urban space is also part of a chance encounter.

AG : Well, I think the chance encounter is a good way to describe it. The scene with a woman in Constructivist Drift emphasizes the disconnect of the urban environment. She is speaking to a camera, but the voice gets drowned in the city's noise. The footage that is projected onto the wall of Chatham tower in this film was recorded during my trip to Moscow and Saint Petersburg in 2016. And as the film continues, the sky becomes darker in the background until you have a rectangle of the screen floating in the city’s night. And once the projection stops, the film cuts to black. The pandemic experience of 2020 of course was a disconnect on a global scale that affected the world socially, politically, and psychologically.

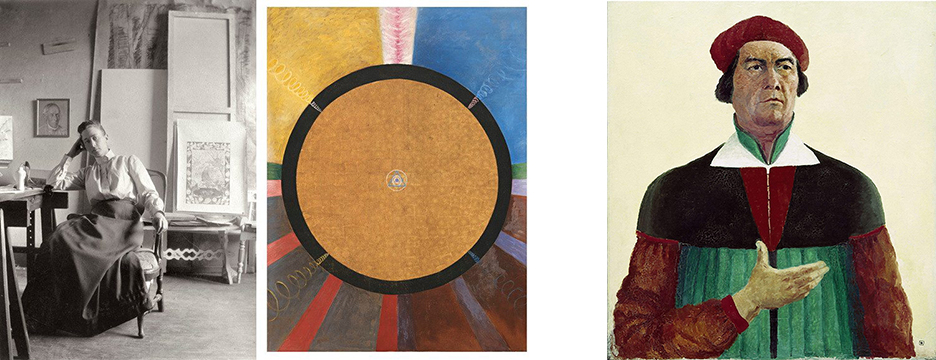

As I was working on the paintings, I was also aware of an apparent reference to the work of Hilma af Klint. Since there have been a few significant exhibitions of her work in recent years (at the Guggenheim Museum, for example), I included her name in the titles of two of the paintings. Her work does have a diagrammatic quality, but they reflect her spiritual experiences; thus, it differs from my project. I'm trying to place each work within specific geographical locations (in downtown New York and also upstate), as well as the events of 2020. There is a good quote in the "Formulary of the New Urbanism", where Ivan Chtcheglov writes that architecture is the simplest means of articulating time and space, of modulating reality and engendering dreams.

KS: That’s a very elegant way of putting it. I can't resist focusing on Hotel of Strangers, 2020. There's a kind of sacred geometry you have there, in the grouping of two works, Hotel of Strangers and Tivoli. A triangle pointed up can be quite phallic, like the lingam; the triangle pointed down resonates with the image of the yoni. They exist almost as an algorithmic translation or transformation one of the other one. The two are not mutually exclusive.

There are certain elements in your palette that stay consistent, although the scale, the level of abstraction, and its complexity vary. Its concreteness gives them a relationship with a shield and also with an icon. I am reminded that, when Malevich was making figurative paintings later in his life, following the dictates of Socialist Realism, he replaced his signature with a black square. In his famous self-portrait of 1933, in the lower right corner, where his signature would go, he put a black square inside a white one. The black square became his signature.

AG: So it is like a modernist emoji.

KS: And a small but important act of resistance, which may have helped him maintain his sanity in a world where the values of non-objective painting, for which he had been celebrated, had shortly afterwards been anathematized. One of the things that Debord did, when he edited the manuscript of "Formulary for a New Urbanism" for publication in the first issue of the SI journal, was to suppress some of the surrealist and mystical elements. At the end of the Chtcheglov’s original text, he uses this word, égrégore, which is taken from a Greek term, meaning a watchman, or one who has been awakened. The term has been understood in French in several ways. One is a kind of spiritual guide (Victor Hugo). Another is a kind of collective consciousness, generated by a group. This is how Chtcheglov uses it in reference to psychogeography.

AG: In the Translucent Concrete body of works, I'm also starting to introduce expanded titles for the paintings, which helps contextualize the works. For example, the title of the exhibition Translucent Concrete is a direct reference to Chtcheglov’s "Formulary for a New Urbanism." The expanded titles serve as micro-narratives that act as metaphoric shadows to the paintings, linking abstraction to my experience.

KS: I’d like to think of our exchange in the same way: crisscrossing metaphoric shadows to your work.

Keith Sanborn is a media artist, theorist and translator based in New York. His artistic practice includes film, video, photography, installation, and performance. That work has been the subject of numerous one-person shows and has been featured in major museum surveys including the Whitney Biennial, the American Century, and Monter/Sampler (Centre Pompidou) and festivals including EMAF, OVNI, and The Rotterdam International Film Festival. He has curated programs for Artists Space (New York), the Oberhausen Short FilmFestival, and Hallwalls Gallery, among others. He has taught at Princeton University, Columbia University, Bard College, UCSD, SUNY, Buffalo and the San Francisco Art Institute. His theoretical work has appeared in journals, books, and museum catalogues. He has translated the work of Debord, Viénet, Wolman, Bataille, Napoleon, Gioli, Brecht, Farocki, Kuleshov and Shub.

Translation best describes his work as a whole: the strategic shift of media from one context to another.

{{title}}

{{year}}

{{medium}}

{{size}}

{{price}}

{{status}}

Clearwater Contemporary Art, LLC (d/b/a “Helwaser Gallery”) is committed to protecting and respecting your privacy. This privacy policy describes the Personal Data which Helwaser Gallery collects about you through your use of our Platforms, and also sets out how we use, disclose, and protect this data. It also outlines your choices and rights regarding the personal information you have provided to us.

This policy applies to all Personal Data processed online by Helwaser Gallery through its website, social media platforms, email, and newsletter subscription service.

For the purposes of this Policy:

“Personal Data” means any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person, where an identifiable natural person is one who can be identified, directly or indirectly, in particular by reference to an identifier such as a name, an identification number, location data, an online identifier or to one or more factors specific to the physical, physiological, genetic, mental, economic, cultural or social identity of that natural person; and

“process”, “processed” and “processing” means any operation, or set of operations, which is performed on Personal Data or on sets of Personal Data, whether or not by automated means, such as collection, recording, organisation, structuring, storage, adaptation or alteration, retrieval, consultation, use, disclosure by transmission, dissemination or otherwise making available, alignment or combination, restriction, erasure or destruction.

What information do we collect?

You may give us information about you by filling in forms when using our services, signing up to our newsletter or contacting us with enquiries. Such information can include:

1. Your name, address, telephone number and e-mail address; and

2. Data including artwork information, artworks owned, requested, offered, reserved, purchased, consigned and details of artwork invoices.

Information about your usage of, and interaction with our website. we may automatically collect data about your browsing activities including traffic data, location data, the originating domain name of your Internet service provider, and statistics on page views.

We keep your information confidential, but may disclose it to our personnel, suppliers or subcontractors insofar as it is reasonably necessary for the purposes set out in this privacy policy. However, this is on the basis that they do not make independent use of the information, and have agreed to safeguard this information.

In addition, we may disclose your information to the extent that we are required to do so by law (which may include to government bodies and law enforcement agencies) in connection with any legal proceedings or prospective legal proceedings, and in order to establish, exercise or defend our legal rights (including providing information to others for the purposes of fraud prevention).

How do we use the information collected?

Your Personal Data is generally processed by us as necessary for purposes directly related to our functions and activities. This includes any one or more of the following purposes:

We also use various forms of marketing to provide you with promotional materials for the purposes of marketing in accordance with our legitimate interests to send you information about gallery exhibitions and events. We use third party email providers, such as MailChimp, to process these marketing emails. If you would like to be removed from this mailing list, please contact us at info@helwasergallery.com or click on unsubscribe at the bottom of each marketing email.

We may share your Personal Data with our selected third party providers and suppliers for the performance of delivering our Service under the contract between you and Helwaser Gallery, including processing payments and delivering artwork to you in accordance with your instructions. Our third party suppliers will have their own processing terms. Where we reasonably believe that you are or may be in breach of any of the applicable laws, we may use your personal information to inform relevant third parties such as your email/internet provider or law enforcement agencies about the content.

Consent

Helwaser Gallery does not process the Personal Data of persons 16 years of age or younger, except where express consent has been communicated to us by a person capable of giving such consent on his/her behalf. Where the processing of your Personal Data does not fall under one of the bases set out within this policy, we will obtain express written consent from you for such processing by methods or means which include making you sign a form or check a box. You can withdraw such express consent at any time by contacting us at info@helwasergallery.com

You have the right to request a copy of the personal information we hold about you and to have any inaccuracies corrected.

We will use reasonable efforts to the extent required by law to supply, correct or delete personal information held about you on our files (and with any third parties to whom it has been disclosed to).

Access to Personal Data

You may request access to, and correction of, your Personal Data held by us by contacting us at the contact details at any time. All requests for access and/or correction will be processed within a reasonable time except where we refuse such requests in accordance with any applicable laws or regulations. In some situations, you may be able to access and correct your personal information directly through our Platforms.

Safeguarding Personal Data

We will use reasonable technical and procedural measures to safeguard your Personal Data, for example, by: ensuring that access to any personal account you have with us is controlled by a password and username which are unique to you; storing your Personal Data on secured servers; and restricting access to Personal Data on a ‘need to know’ basis.

Whilst we will use all reasonable efforts to safeguard your Personal Data, please note that the use of the Internet and/or our Platforms cannot be made entirely secure and we therefore are unable to guarantee the security or integrity of any Personal Data which is transferred from you or to you via the Platforms.

Object to us processing data about you

You can ask us to restrict, stop processing, or to delete your Personal Data by contacting us at info@helwasergallery.com if:

If you inform us that you would no longer like us to store or process your Personal Data, we may be required to collect information from you each time you interact with staff members or through our website.

Making a complaint

If you are unhappy with the way Helwaser Gallery is processing your Personal Data, please let us know.

By email: info@helwasergallery.com, referencing “Privacy Policy”

By mail: Helwaser Gallery, 833 Madison Ave, Third Floor, New York, NY 10021

Data retention

We will hold your personal information on our systems for as long as is necessary for the relevant service or as required by law, or for accounting or regulatory purposes, or as otherwise described in this privacy policy.

Changes to our policy

We will notify you of any changes to this policy by email, or announcing it on our website.

Further rights of data subjects in the European Union (“EU”)

If you are a data subject in the EU, you may contact us to exercise the following further rights:

All requests made to us in exercising the rights above will be processed within a reasonable time except where we refuse such requests in accordance with any applicable laws or regulations.

Updated August 2019